Through an organic, interdisciplinary approach, Maya’s work comments on gender and racial inequalities that pervade Indian society. She employs tangible real-world materials to convey thoroughly researched ideas that poke holes in unquestioned, but question-worthy, notions.

About fifty miles from the famed Taj Mahal lies the lesser known North Indian city of Firozabad. Romanticized as the “City of Glass”, it’s the largest producer of women’s glass bangles in the country. It also happens to be located in the state of Uttar Pradesh, which has the highest incidence of crimes against women in India. When artist Maya Jay Varadaraj discovered these two seemingly disparate facts, she set out to connect the dots.

In her project *Khandayati *(in Sanskrit, “to break”), Maya holds a microscope to the custom of Indian brides wearing glass bangles to preserve their husbands’ health and prosperity, a practice she views as a symbol of oppression. These bangles are thought to represent a groom’s well-being, and wives are expected to keep them on and intact to ward off bad omens. If her husband dies, the widow must break her bangles as an act of mourning.

For the project, Maya used typical household appliances like a grinder, vacuum, and microwave to create a system that crushes and melts down glass bangles, reforming them into similarly-shaped chakras that signify female power. It’s concrete and noisy and feminine and deeply visceral.

Maya’s focus on women’s issues stems as much from current events as it does from problematic long-held traditions. She was initially moved to take action when she read about an incident of gang rape in Uttar Pradesh that led the victim to commit suicide. Maya said, “The perpetrators videotaped the incident and circulated it around the village. The victim approached administrators and her support system for help, and they said ‘no, this is your fault and you have to live with this.’ She could no longer function in that society.”

This came after the Nirbaya incident which made global headlines in 2012. “It was baffling that after such a traumatic experience for a country, it still allows for women to be treated like this,” Maya said. “I researched Uttar Pradesh and found that it has the highest incidence of gang rape in the country, and that Firozabad is the largest manufacturer of glass bangles. I looked at the history and realized there’s a connection to violence and subjugation, and I wanted to explore that.”

Also as part of Khandayati, Maya modified mass-produced calendars depicting idealized imagery of women in the home, aiming to show a parallel deconstruction of this domestic identity. In its entirety, the project not only commented on patriarchal gender norms that remain largely unanalyzed but also on the life-and-death issue of violence toward women.

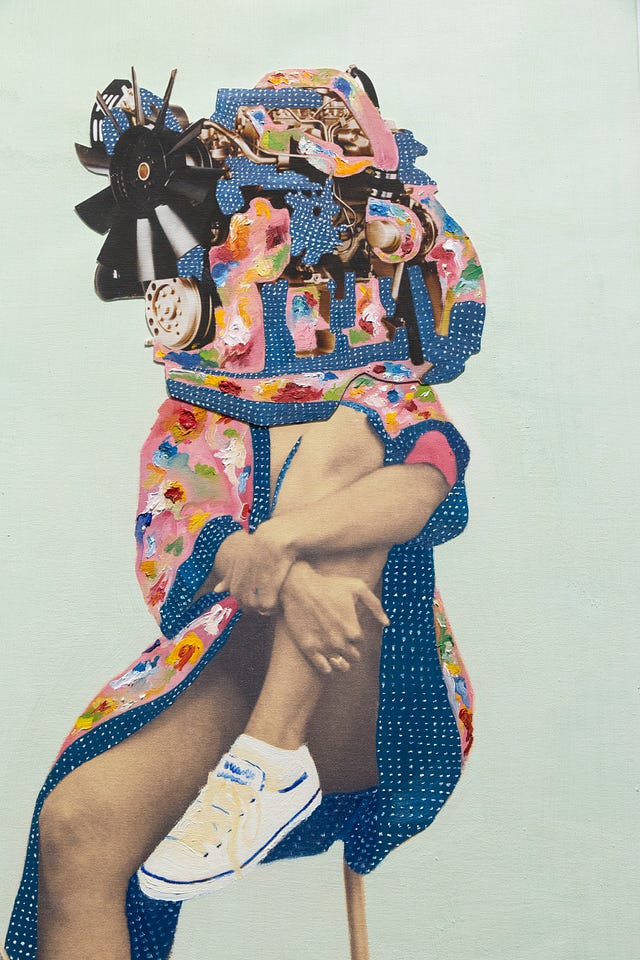

As a woman of Indian descent myself, Maya’s work struck a chord with me and I was eager to learn more about her past and current endeavors, including an exhibition that’s up now at Mana Contemporary in Jersey City. The exhibit, titled The Woman and The Machine, builds on the ideas underlying Khandayati and features mixed-media collages and painted photographs that shed light on domesticity and violence in the lives of Indian women.

“The Woman and The Machine uses quintessential imagery that many Indian households have as a way to enter the domestic realm and change perceptions,” Maya said. “I’m excited to see how people react to seeing this idyllic imagery being taken apart.”

When I got on the phone with Maya, she was just four days away from the exhibit’s opening, but she took a break from toiling away in the studio to talk to me about her creative life and her path from Tamil Nadu to NYC.

Curiosity takes shape

Hailing from Southern India, Maya is well-versed in the religious and cultural norms that contribute to India’s complex and deep-rooted systemic disparities. Her liberal upbringing, however, equipped her to think critically about what she saw. She attended an international boarding school that encouraged diversity and her progressive parents treated her as an equal to her two brothers, but she understood this wasn’t the case for many young women coming of age in India.

Maya has always known it’s possible for the playing field to be leveled based on her own microcosmic experiences. Rather than opening viewers’ eyes up to how things could be, then, she focuses on showing how they should be from her vantage point.

“I was always exposed to a multitude of cultures and religious practices,” she explained. “So my point of view comes in the ways that I feel different in situations. If I can’t identify with a situation but I care about it, that’s where I find gold. That’s where I can share my circumstances and perspective. It might not be the perfect, right perspective, but it is a perspective.”

Maya remembers becoming attuned to societal issues at an early age and channeling her feelings about them through art. As young as five years old, she would “incessantly” draw images of religious architecture in response to the blatant tensions between Muslims, Hindus and Christians in India. She was able to view these conflicts objectively thanks to her parents’ open mindedness: “Some of my extended family was religious in the Hindu faith, but at home we didn’t adhere to any of that. My mom took us to church, she took us to temple, and we would learn about all religions.” Maya discovered that, through creative expression, she could manifest the changes she hoped to see in her surroundings.

Though she doesn’t pinpoint a singular “a-ha” moment as the beginning of her journey as an artist, Maya cites her parents’ acceptance and encouragement as laying the foundation. “My parents always told me to do what I wanted to do. Get good at it, commit to it, and be what you want to be. There wasn’t pressure this way or that. It opened up a lot of choices,” she explained. “So I just realized I was good at [art] and I enjoyed it. I set this goal of getting accepted into [Rhode Island School of Design (RISD)], I achieved that, and from there it progressed.”

At RISD, Maya began working toward a BFA in Apparel Design. Like most undergraduates, she didn’t fully recognize what this path would entail long term, but focused on putting one foot in front of the other. “When you’re young and going into college, your priorities are all over the place. You’re trying to

find what you’re interested in and what’s important to you. I came to the States because I got into RISD and I was happy to start developing work in fashion and design,” she said. “But I realized that especially in educational institutions, design and art are two very different things. The processes, the way of thinking and producing, even the linguistics are totally different.”

This realization marked an unconscious start to Maya’s development into an interdisciplinary creator. After graduation, she moved to New York to work in the fashion industry, viewing it as an opportunity to pursue a lucrative career in a creative field. “I come from a culture where working, getting a job, being successful, making money is important,” she said. “But I was looking for a professional experience that could also teach me something. So I was like okay, here’s a new thing to learn.”

In two years of working in fashion, though, her restlessness grew. “I had learned so much and worked with incredible people, but I knew there was more that I needed to achieve and say on my own,” she said. Her solution to this internal conflict? Graduate school. She wanted to study three-dimensional design holistically, so she applied and got into the Art Institute of Chicago’s MFA program in Designed Objects, intending to make furniture or products inspired by larger philosophical ideas. But expectation and reality diverged again as Maya came to terms with the inherent insincerity of making commercial products as a means to discuss deeper subjects.

“I realized that making products wasn’t the right outlet. There was a trend in design where furniture or functional objects had this feeling of coming from a place of higher thinking, and I found that to be inauthentic and couldn’t allow myself to enter that space,” she said. “I felt like there was more that could be research-based and that could go into the history and ontology of objects versus the making and posing of them as something they’re not.”

Maya thus focused on understanding theories around objects and discovering new creative channels. This was another step toward a fluid, mixed-media approach to art. I asked Maya where she thinks that interdisciplinary instinct came from. “It was my reaction to being constantly asked whether my work was art or design, and feeling like that was an irrelevant question because I never wanted to be in either of those boxes. It felt detrimental to exploring and learning,” she reflected. “It just occurred to me that I was interdisciplinary — that my work is not just art, not just design. But my focus is on my work being well-researched, authentic, and coming from a place where I’m able to share something that’s not insular, but socially engaging.”

Principles to processes

Cycles are prominent in Maya’s growing oeuvre — with each piece, she strives to close a loop. Khandayati was a manifestation of the cyclic nature of her work; seeking to contribute to the discourse about the portrayal of women and domestic machines, the exhibit repurposed appliances to reclaim the very things she was destroying. Her painted photographs and collages are further evidence — she acquires imagery that’s emblematic of an outdated hierarchy and reinterprets it, flipping it on its own head.

When Maya talks about the importance of studying as part of her process, she means it. “I research materials, the history, chemical properties. If it’s a narrative I research the surrounding circumstances to understand the larger context of how it exists and where it exists. That informs the statement I want to make, what it looks like and the components of it,” she said.

After the research phase, her process includes equal parts tinkering and introspection. Of Khandayati, she said, “My favorite part was being acquainted with the machines: taking them apart, putting them back together, making sure they work. Understanding the innards. It created this relationship between me and the machine. In that context, I viewed myself as ‘the woman’ versus me as Maya.”

One of my takeaways from our conversation was that Maya seems to continually evolve and build off of past ideas, taking them in new and different directions. In this way her process tends to mirror the work itself — repurposing, recycling, reinterpreting. “The Woman and The Machine was informed by Khandayati,” she affirmed. “It’s another perspective on machines and domesticity. Each project definitely informs the other.”

Art as activism

There is no question that Maya seeks to convey certain messages through her work, but I was curious to understand whether she views her art as an educational tool, a vessel for galvanizing people into some kind of action, or if she believes viewers should be free to decide for themselves.

“I certainly want my work to exist in the larger context of social movements, especially for women in the South Asian diaspora and South Asia in general, so I have to be aware and deliberate with the choices that I’m making,” she said. “For Khandayati, I had to think about how every choice informed the larger message: what the objects were being placed on, what color the stands were going to be, whether they were going to be put in acrylic boxes or not. Everything had to be intentional because it was not just about my perspective, but a bigger group’s.”

Creating thoughtfully doesn’t mean spoon-feeding the audience, though. With The Woman and The Machine, Maya isn’t enforcing a way of interacting with the exhibit, though it is structured in two parts with curatorial text in between. “The way people move through it organically will inform what I do next and give me ideas. I’m excited to see how people respond to it,” she said.

Discovering home across the world

For Maya, moving back to NYC after completing her master’s program was a natural choice. She gravitated toward it not just for its diversity and exuberance and opportunities, but also its familiarity. “New York feels like home in the way that India does because of its crowds and it smells and its congestion and its dirt,” she said. “It’s a place where people are accepted for who they are, what they are, what they do, how they do it. I’m happy to be back.”

Working with Nooklyn agent Andrei Kunevsky, Maya and her husband landed an apartment in Manhattan’s Upper West Side where they now reside with their two cats. She commutes daily to her studio at Mana Contemporary in Jersey City, which she has also developed an appreciation for. “It’s interesting because it’s close to a large Indian population,” she said. “My path to Mana is literally like walking through R.S. Puram at home. It’s charming,” she said.

I asked Maya what her days are like as an independent creative. “A productive day starts with two large cups of coffee before taking my hour and a half long commute,” she laughed. “When I get to my studio I orient myself, set goals and work through them. Committing to a creative field is difficult; there are never any right answers. It’s never like, one plus one is two. One plus one could be 35!”

At the end of each day, though, she strives to take a breath and feel satisfied by whatever she’s accomplished. “I clean my studio and make sure everything’s in order, and when I get home I relax, spend time with my cats and recap my day with my husband.”

Onward

She’s early in her career, but Maya’s repertoire of skills and achievements is already impressive. She is a badass example of an immigrant with an advanced degree who works in an unconventional field and uses her craft to expand the consciousness of her community — and in the process, she’s undoubtedly carving out her own spot in New York’s art scene.

Maya is part of a small group of burgeoning South Asian artists in the diaspora, but she hopes to see it grow. “I’ve been thinking about how few women from South Asia pursue art and creativity. There are a lot of South Asian artists in South Asia, but not many from the diaspora,” she thought out loud. “I think it has to do with learning that creative expression is valid. It’s important for creating an identity and confidence, and it opens up platforms for political and social discussions that don’t necessarily exist for us.”

The Woman and The Machine will be on display at Mana Contemporary until June 7th. Keep an eye out for updates by following Maya on Instagram — she will be rotating new pieces into the exhibit at its halfway point in April. In the longer term, Maya will continue building on what she started with *Khandayati *by analyzing other materials prevalent in South Asian households and the underlying conditions they represent and create, and using her process-driven, multimedia framework to generate scale, movement and impact.

Despite turning a critical eye toward India, it’s obvious how much Maya simply loves and wants the best for her home: “There’s so much beauty in our culture. There are such strong philosophies. But they’re looked over because of the political and social obstacles that keep us from thinking about them.”

Learn more about Maya Jay Varadaraj’s work here and share your thoughts with us on Instagram!

Photo Credits:

Photo by Nicole Stoddard

Photos by Jonathan Allen

Photos by Ambika Singh

Photo by Nicole Stoddard

Photo courtesy Maya Jay Varadaraj

Photos by Ambika Singh

Photo by Stephanie Bassos