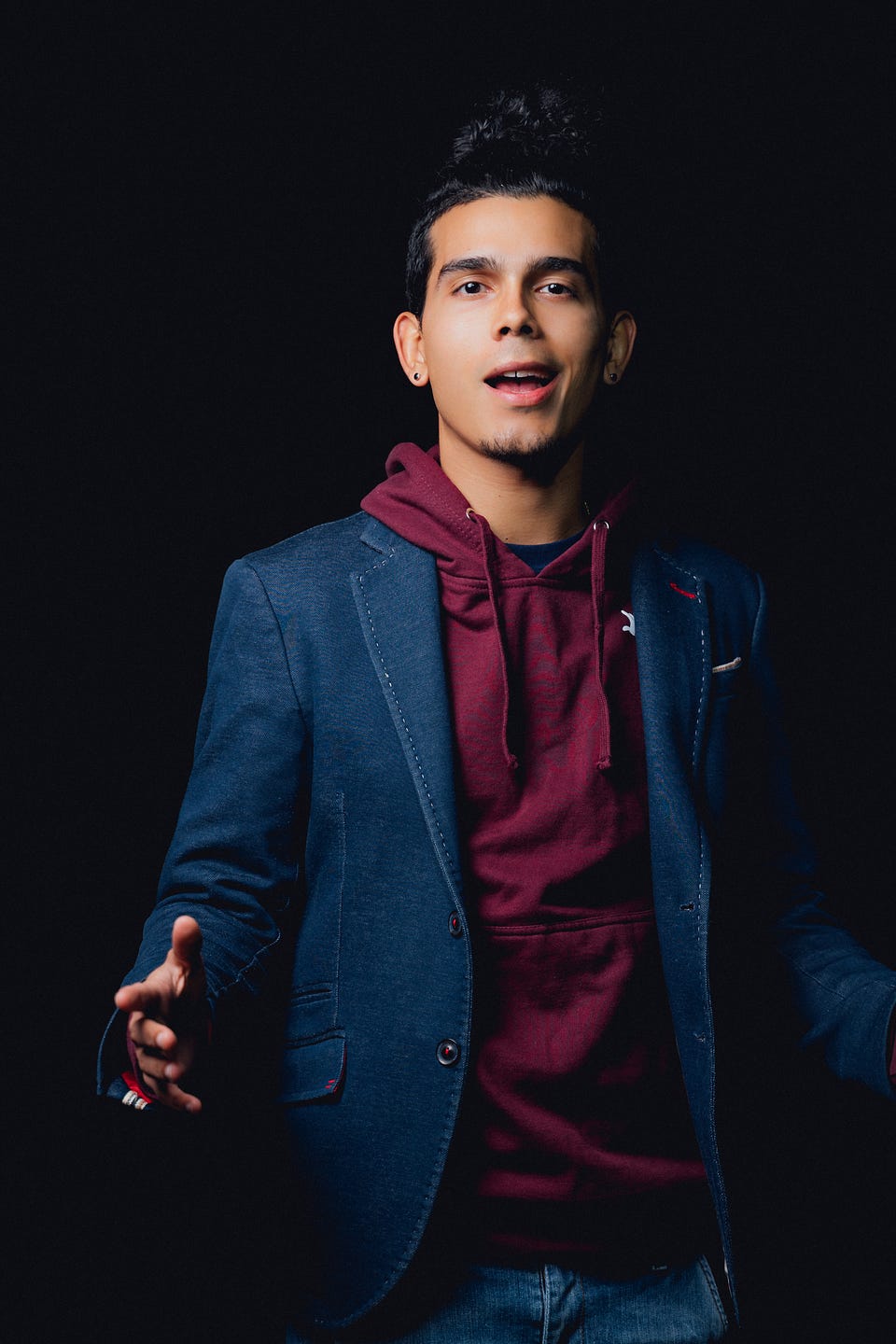

There is certainly no shortage of ambitious, passionate and energized New Yorkers, but it’s rare to encounter someone who directs as much of their time and energy toward making a concrete positive impact as Bronx native Noel Quiñones. Equal parts award-winning spoken word artist and local activist, Noel’s work is fueled by a connection to his home borough and an exploration of his Afro-Boricua heritage.

When I say Puerto Rico I mean an opening in the skin

where gold turns green under my scalp.

This type of call is very common,

María, like a buzzsaw, shaving off the top of the island

Noel’s words elicit a visceral feeling in the listener, the reader. He writes and emotes with a tenderness and a candor that work in harmony to convey deliberate messages and themes. His poetry covers a spectrum of topics, including Puerto Rico’s fraught history and ongoing plight; growing up with divorced parents; the nuances of his cultural identity; and “punk rock, comic books, joyful things.” He contains multitudes.

When I met with Noel most recently at a midtown Gregory’s Coffee, he was in the midst of a hectic week balancing his day job as a high school administrator at Brooklyn Friends School, planning events for the Bronx-based arts organization he founded called Project ‘X’, and continuing to write and perform poetry. He had also recently received his acceptance into the University of Mississippi’s MFA program, which he will be starting this fall. Naturally, there was plenty to discuss — and I’d be remiss not to shout out the Gregory’s employees that allowed us to stay a touch past closing time to complete our conversation about Noel’s path to artistry and activism.

Discovering heritage alongside creative expression

Both of Noel’s parents are Puerto Ricans who grew up in New York and both of his grandmothers migrated to the city in their youth, making him a third generation Nuyorican. His mother and father divorced when he was a toddler, so his childhood was split among four different homes in the Bronx. Noel attributes much of who he has become as an artist to this experience and the stories he was told by each influential figure in his life, particularly the narratives around cultural preservation and upward mobility.

“The Bronx that my dad and grandmother grew up in is not the Bronx that I grew up in. He grew up in a Bronx that was very tough. There was violence, drugs, death,” Noel explains. “I grew up in less proximity to those things, but my parents raised me to believe that the Bronx was somewhere you escape from, somewhere you leave.”

When he turned thirteen and was preparing for high school, both of Noel’s parents moved to Queens. But because he had earned a scholarship to attend a prestigious school in the Riverdale neighborhood of the Bronx, this meant he had to endure a two-hour daily commute from Flushing. His mother also kept her job teaching second grade in the South Bronx, so Noel recalls being frustrated and confused about the move. “I was thinking, all my friends and family were still in the Bronx, why are we doing this? But it was very much that hard set… ‘this is not the life we want for you. We don’t want you in this borough,’” he recounts.

This imperative became imbued in Noel’s mind, not dissimilar to how his grandmothers, who were each under 10 years old when they migrated, came to view leaving Puerto Rico. “My dad’s mom will always say she never wanted to come here, she loved Puerto Rico and she remembers it vividly,” Noel says. “I’m working on some poems about her childhood, so I interviewed her a few months ago. She remembers getting off the plane here and it was freezing, and she was like ‘why are we here?’ But it’s because her stepfather believed there were better opportunities here.”

Puerto Rico is an unincorporated territory of the United States; its residents are legally recognized as American citizens but lack certain freedoms, most notably the right to vote in federal elections. The island has faced decades of economic instability in the absence of proper sovereignty, which has generated an ongoing migration of Puerto Ricans to the States. Noel’s family is one of many in this diaspora.

Despite being a few generations removed from the island, Noel recalls Puerto Rican culture being at the forefront of his upbringing. When I ask what that looked like, he bluntly describes it as “the go-to cultural things people say you’re supposed to be proud of, like the food and music and dance.” For example, a Puerto Rican Christmas tradition called La Parranda: “You go door-to-door singing carols, and every house you go to feeds you so it’s this whole beautiful community thing. My mom did it every year even though we were in New York,” he says. “My dad was also very big into salsa dancing, so I remember growing up with the music.”

Like many children of migrants in the United States, Noel was not raised bilingual. “My mom’s mom remembers being spit on when she came here for speaking Spanish and not knowing English,” he says. “So she didn’t want to pass it along.” Noel’s mother thus had to learn Spanish on her own and lacked the confidence to teach him. He’s still learning.

Going from an inner city Catholic school to an elite secondary school was a “complete culture shock” for Noel. In middle school, “everybody looked like me. And it was a few blocks from where I grew up,” he says. “At this new school I was one of, like, six Latino kids. But the reason I went deeper into my Puerto Rican roots was because I was othered so much. Everybody was like who are you, where are you from? I remember my first year, someone told me to go back to the country I came from, and it was like… We’re in the Bronx. I grew up here.”

Noel started writing the summer after ninth grade while attending a summer camp in Pennsylvania. He’d always loved reading — he recalls spending quality time with his dad at Barnes and Noble — so he signed up for the camp’s creative writing workshop. The instructor equipped the students with a notebook and tasked them with writing an original poem every day for two weeks. By the time Noel began tenth grade, his book was full.

Then, in a history class, Noel briefly learned about the Nuyorican poetry movement, something he hadn’t been aware of previously. This was a pivotal moment for Noel, marking the beginning of an in-depth exploration into his cultural identity. “I didn’t know any Puerto Rican history, good or bad. So I spent junior year of high school teaching myself,” Noel remembers. “That’s when things changed for me and why I got so invested. I ended up knowing more than my parents and grandparents about the history of the island. And bridging the good things they gave me — the music, the food, the culture, with the not-so-good things — the history of colonization.”

Finding his voice

As he began writing, Noel was going through that charming period of teenage angst most people can relate to, which he channeled into “terrible high school poetry” inspired by the emo and punk rock music he liked. “I spent tenth grade writing poems mostly about being a teenager and about the Bronx. I hid the notebook at the bottom of my dresser and didn’t tell anyone I was writing. But I came home from school one day and my mom was on my bed reading the poems,” he laughs. “She was like ‘oh my god, did you write these? These are good!’ And I was like ‘no, they’re terrible!’ But I’ll forever thank my mother for being the first person that publicly validated me and said they were good, when they were not good.”

The confidence his mother instilled that day led Noel to eventually share his work with a friend, who told him about a little thing called Def Jam Poetry on HBO. “She pulled up YouTube and showed me Mayda del Valle, who’s a famous Puerto Rican poet from Chicago. And that was it,” Noel says. “I had never seen someone who looked like me do something that people called a poem. All the poetry I was taught in school was by old, dead white people. So I saw this person who was Puerto Rican, doing a poem about being Puerto Rican, and I was like I’m hooked. I want to do that.”

During the latter half of high school, Noel got involved with youth poetry organization Urban Word NYC. He attended free workshops and began competing and performing spoken word. It was through this experience that he began incorporating Puerto Rico and his identity into his poetry.

After graduation, he landed at Swarthmore College in Philadelphia with a clear vision in mind. “My friends made fun of me because I was one of the few people that showed up and knew what I wanted to do from the beginning — English Literature, Creative Writing and Education,” Noel says. “I started Swarthmore’s competitive spoken word team and took us to our first nationals my freshman year. I just knew what I loved and wanted to keep doing it.”

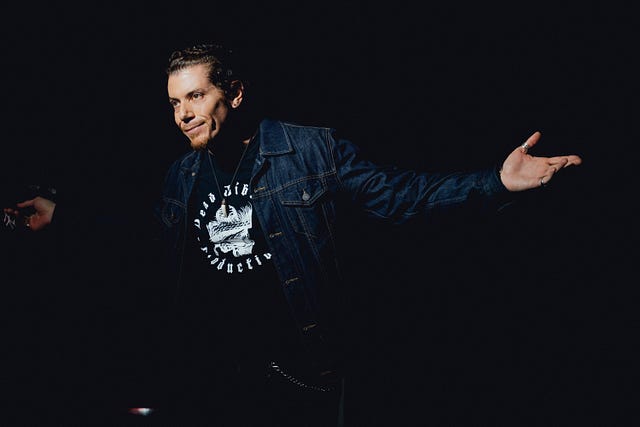

Noel also knew he wanted to end up back in the Bronx after school, so he moved back in with family and got a job at a local nonprofit. But he was most excited about diving into the NYC slam poetry community. Though the city was where he’d initially found his voice, he had come into his own as an artist in Philadelphia. Upon returning, he participated in several prominent certified slam competitions — the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, the Bowery Poetry Club, BRIC in Brooklyn, and Union Square Slam. But as he became immersed in the community, he quickly recognized aspects of it that didn’t sit right with him.

“I noticed that I was either the only or one of two Latinx slam poets who were sharing content about being Latinx. I’d get little comments, like someone said ‘I would’ve scored you higher if you had less Spanish in your poem.’ Which happened at the Nuyorican!” Noel exclaims. “It devastated me, because I had been like, I’m gonna be a Nuyorican poet doing Nuyorican poems at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe… and then that happened.”

At one point, Noel had made it to the Grand Slam Finals at the Bowery Poetry Club along with another Latinx poet. “It was ten people competing for four spots and someone taps me on the shoulder and they’re like ‘good luck, because there’s only going to be one of you — they won’t take two Latinos on one team.’ I was like, this is a community that’s supposed to be inclusive.”

When Noel made the Bowery team and the other Latinx poet didn’t, “it was this affirmation that they only wanted one of us. So I spent the summer of 2016 on the team wondering how that happened, what my story meant.” Reflecting on his trajectory within the spoken word world, Noel realized that as a young, malleable artist he had often been pushed into narrow way of thinking. “They tell you that you have to find your big selling identifier — race, ethnicity, gender, class, sexual orientation,” he says. “In high school and college, I thought I could only write about being Puerto Rican and also that it had to be sad. So a lot of my early work was about how shitty Puerto Rico’s history was, and about my parents’ divorce, which I was painting in a bleaker light than it actually was. I was told I had to write in a certain way and about a certain thing in order to get points to win competitions.”

When I ask Noel what has evolved in his work since those revelations took place, he takes a beat before replying: “Only in the past two or three years have I been able to write what I want to write. It’s led to more quiet poems, happier poems about more obscure things,” he says. “I’ve grown in terms of what I can allow myself to write about. And also coming back to writing about Puerto Rico and divorce and my parents, but in a more three-dimensional way, showing the good and the bad.”

Activism and Project ‘X’

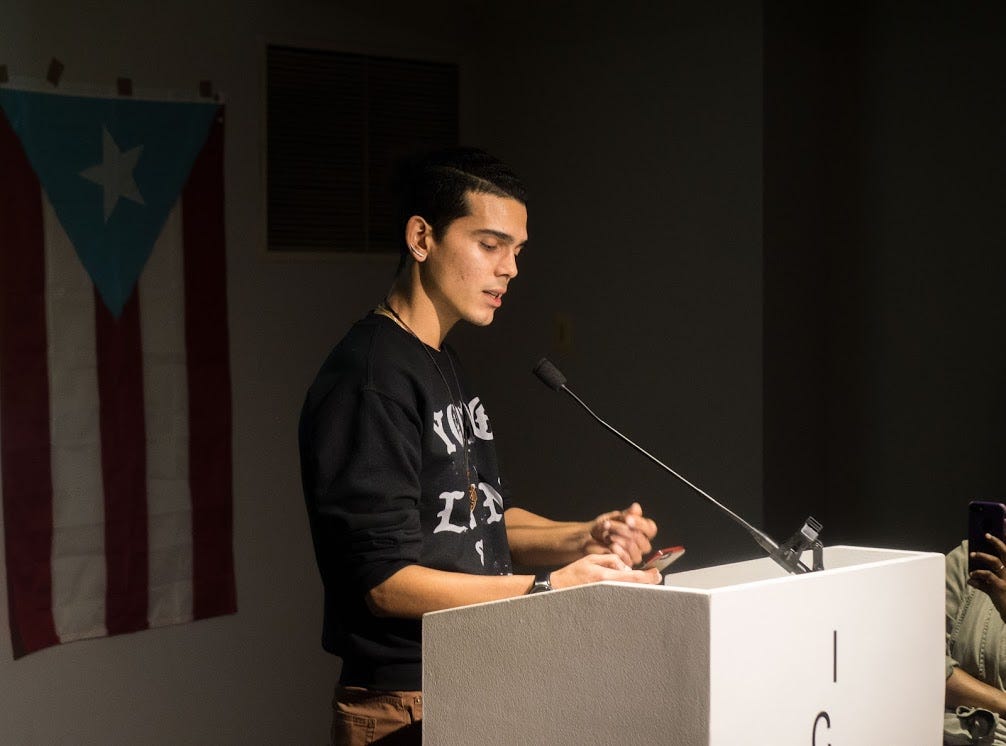

After these vital realizations, Noel knew he had to do something to promote inclusivity in the poetry community. He decided he wanted to create a space for Latinx poets to express themselves freely: “Latinx poets shouldn’t feel ostracized for using Spanish, for talking about their narratives, for being who they are,” Noel says.

Recognizing that there had never been a certified slam venue in the Bronx, he became determined to create a safe environment there for Latinx artists, and the idea for Project ‘X’ was born. Noel wisely looked to the community to shape the organization’s vision. “I brought together friends, family, organizers, artists, poets, and I was like ‘hey, do you think we should do this, and would y’all help?’ And everyone was like, ‘let’s do it’,” he says. The organization launched in February 2017 with a big showcase at the Hostos Center for the Arts & Culture in the South Bronx.

This wasn’t Noel’s first foray into community organizing; it had been brewing within him since childhood. “I made the connection recently that my mom is like, you know that person in every family who brings the family members together?” Noel reflects. “She would host holidays and tell everyone where to go and what to bring. And the connection I made was… that’s event planning. That’s community organizing.”

The real-time impetus for Noel to dive into activism was when he received his high school scholarship. As he was graduating from eighth grade, he saw that he was the only one from his middle school going to an independent school. And as soon as he arrived there, he was overwhelmed by the myriad of resources and opportunities the school offered its students. He immediately asked himself, why don’t people back home know that this exists?

“I know now that I was blessed to have my father, he was the first person in his family to go to college and he fought for my education aggressively. He found out about independent schools and knew I needed to be there,” Noel says.

Noel promptly went back to visit his middle school and asked if he could give a talk to the students, informing them about the accessibility of these opportunities. “That was my first moment of activism. Being like, I know that I got an opportunity that other people like me are not allowed to have, and that’s messed up,” Noel says. “It kept going from there. I led the Latino student group at my high school, and then I got to college and kept taking on these roles and wanting to change things.”

Project ‘X’ is now in its third season and Noel is happy to report that it’s grown steadily each year. “We started with just the Latinx focus but we wanted to open up to all Bronx artists,” Noel says. “Our first year we competed at the Northeast regional, and the next year we made the national slam team that competed in Chicago against teams from across the country. We made history — it was the first-ever Bronx team to do that.”

On the local front, the arts organization hosts slam events every last Thursday of the month featuring both Latinx and non-Latinx poets in “a celebration of people coming together.” But Noel wanted to build a community that goes beyond spoken word; last year, Project ‘X’ spearheaded several monthly events: an immigrant open mic to raise awareness about DACA, a hurricane relief fundraiser for Puerto Rico, a DJ battle Christmas party, a fashion show, a healthy eating workshop, and a women’s empowerment event.

But after two years of going full speed ahead, Noel and his co-organizers decided to reevaluate their programming this year. “It’s a grassroots organization — we don’t get paid, and we had this tough moment last year where we were like, we did a lot of important work but we’re so tired.”

In order to take a step back and target its efforts, Project ‘X’ is pulling back on monthly events this year and reinvesting in a block party tentatively called the Bronx Poetry and Arts Festival, slated for August 10th. They’ve also launched a free, public professional development series called “La Sala,” encompassing workshops across photography, poetry, and even grant writing.

Work and play in NYC

As a born and bred New Yorker who returned to the city promptly after leaving for college, it’s obvious that Noel loves it here. However, he’s critical of what he calls its “borough culture,” in which people young and old alike stick only to the neighborhoods they live, study, or work in.

Noel credits his mother for ensuring he broke out of his bubble and explored the city as a kid. “She was a teacher at work and at home. We were always traveling — we would get on the train and go to every museum, every tourist landmark. She was big on the idea that New York City is a classroom.”

Now, Noel applies this to his role at Brooklyn Friends School. He runs its “Creativity, Activity and Service” program, which replaces the traditional community service model with an initiative that actively combines student interests with service. “We ask students, what are you passionate about, what do want to try, and how can you use this to help people?”

Because his position requires him to be constantly researching workshops and activities for young people across boroughs, Noel’s appreciation for the plethora of learning opportunities the city can provide has grown. “I’m excited about all the things you can do here. You can find your niche culture, and also try things you’ve never tried before.”

When it comes to the Bronx and other outer boroughs, he strives to promote how much access to natural beauty there is. “I grew up with parks and nature like the Bronx River Forest. People don’t think of that when they think about the Bronx,” Noel asserts. “Especially in Latino culture, you’re not raised to be outdoorsy, especially in New York. Organizations like Latino Outdoors are trying to get Latinos more into nature.”

Noel hopes that he’s doing his part to get his students outside both within and out of their boroughs. “They can jump on a train with a student pass and go anywhere, but that’s not what they’re socialized or told to do,” Noel says. “So I’m like, what do you like to do in your borough? Even if those things aren’t worthy of being on Time Out Magazine’s top ten list. For example, there’s a big park and barbecue culture in the Bronx — that’s community building.”

Mantras for young artists

Given that he became an artist as a teenager and now works with high schoolers, Noel has a lot to say when I ask him for words of encouragement or advice he might share with aspiring young creatives today.

He stresses the importance of digital exploration: “If you can’t find your community in person, it exists online. I found Urban Word NYC through Facebook. Facebook’s not cool anymore, but even the newer platforms have digital communities forming where you can see yourself.”

Based on his own experience piecing together Puerto Rican history on his own in eleventh grade, Noel tells students, “if you can’t find people doing what you want, make your own textbook. Do the work.”

But Noel asserts that it’s important to also remain open to evolving and continuing your exploration. “Find different versions of the thing you want to do. My biggest upset early on was that I found only one version of slam and it made me do work I wasn’t super proud of. I didn’t find the people who weren’t the norm until later,” he says. “Also, be cool with yourself not being cool. Write the weird poem about alien dinosaurs.”

Bridging past and present

Noel’s decision to pursue graduate school stemmed from the intense burnout he was beginning to experience last year. The forthcoming opportunity will enable him to carve out the time and space he needs to develop creatively: “I had to take a step back and say okay, what do I actually want to do with my time, because it’s split in six different ways right now. And the truth is, I want to write. I want to focus on that.”

But until Noel moves down South to get working on his Master’s degree, he is continuing to work, write, perform, and support the Bronx’s thriving arts community with as much enthusiasm as ever. He’s also confident in his plan to return to the city after graduating.

“I’m always going to come back to New York,” he says. “I just want to take a break somewhere with less distractions, less people. And it’s a fantastic program that’ll allow me to keep touring.”

Noel is thrilled about the project he will be focusing on during his graduate studies, which brings his past experiences full circle. Back when he was familiarizing himself with Puerto Rican history, he discovered that his great-grandfather was a member of the Borinqueneers, the first and only all Puerto Rican military battalion of the U.S. army.

“He fought in the Korean War and was captured and never heard from again. This was also a reason my grandmother and her mom came to America. For her whole life, she wanted to know what happened to her father,” Noel elaborates. “Once she retired she got into Facebook and connected with groups trying to find information about this. It became a big campaign.”

As the search for answers about the Borinqueneers gained visibility, President Obama retroactively awarded medals to the men, including a posthumous Purple Heart for Noel’s great-grandfather. “He also un-redacted the military files about them. My grandmother got a stack of files about her father, which she let me copy. So I’m turning his records into poems — that was the project I pitched in my grad school applications,” Noel describes, his voice laced with excitement. “I have big plans. I just need more time.”

**Check out Noel’s website

Photo Credits:

1-2) Chris Setter

3) Jeremy Rios

4) Shantel Edwards

5-13) Chris Setter

14) Jeremy Rios